This was my 24th time at the Masters and probably the last. With that in mind, I walked every yard of the 18 holes on Sunday, one more body in the Mississippi-sized river of humanity that flowed alongside Rory McIlroy. Forty-seven years on sport’s beat and then to feel like a guest at the Wedding Feast at Cana where the best wine is saved until last.

I have walked the course more than 100 times, known which crosswalks to take, the best vantage points on every green and understood the precise moment to move on to the next hole. Stay at the head of the river and there are things to see, shots you know you will remember until the day you die.

Our press badges confer no privilege on the course. Except for the grandstand to the left of the 15th green with the pond in front. This is the single-best place on the course to experience a moment of Masters drama. At the back of the stand there is an entrance for Augusta National members and press. At the top, I had a perfect view of the green, the pond and McIlroy as he stood on the left side of the fairway, blocked out by the pines. He had 209 yards to the flagstick.

The grandstand beside the 15th green is one of the only places where Walsh was guaranteed a good view

AP

American fans around me were rooting for the Northern Irishman, their allegiance apparent from the first hole. “He’s gotta lay up,” said a young man near by, “crazy to go for it.” I’d seen Vijay Singh play this shot at my first Masters in 2000, going for the green with a high, swinging draw that started on a line 60 metres right of the target but then arced left and came to rest in the heart of the green. That birdie got Singh’s right arm into the Green Jacket. The rest would follow.

McIlroy sees the same shot and plays it just as beautifully. As soon as he’s struck the shot, he marches forward. He knows. Starting way right to avoid the pines, the ball swings left towards the green, dropping on the right side before taking the slope and wending its way towards the cup. Seven feet for eagle.

As he walks towards the green, the gallery erupts, “Ro-Ree, Ro-Ree, Ro-Ree.” This is something never heard at the Masters, football-like chanting at Augusta National. It didn’t happen for Tiger Woods during the great moments of his five victories, and didn’t happen for anyone else. A young woman in a white dress, at the front row of the stand across from where I am, joyously jumps up and down.

Please enable cookies and other technologies to view this content. You can update your cookies preferences any time using privacy manager.

Acknowledging the support, McIlroy flicks the handle of his putter forward, a gesture of defiance like punching the air, as if he too thinks this is the moment. I’ve got this. Too soon, by far. You are Rory McIlroy, the player whose golf psyche is as complex as human nature itself. A psyche in which genius and demons live side by side, locked in a constant battle. Neither gives up. In McIlroy we see part of ourselves, humans with things to overcome. It is why he has become so loved.

So when he flicks the putter forward, it is as if to strike down the demons. But this isn’t possible. Cut off the monster’s head, another head instantly grows. McIlroy doesn’t know and we don’t know that Justin Rose has birdied the 16th to go to 11 under, and it is the Englishman who is now leading the Masters. But here is the eagle putt, needing just the lightest touch of the putter to leapfrog Rose, but . . . this is Rory. The putt is weak, tentative, turning away from the hole before it’s halfway there.

Eagle becomes birdie and an opportunity is squandered.

There is one part of this Sunday at the Masters that will always induce a sense of wonder. McIlroy’s playing partner is a very popular American, Bryson DeChambeau. As they walk to the 1st tee, the home crowd is predominantly for the Irishman. But McIlroy, you see, now transcends geographic boundaries. He’s the Universal Soldier of Buffy Sainte-Marie’s song.

“He’s five foot-two and he’s six feet-four

He fights with missiles and with spears

He’s all of 31 and he’s only 17

Been a soldier for a thousand years.”

I stand at the back of the 1st green and see him getting in and out of the fairway bunker where, feeling weak and wobbly on the tee, he put his drive. From the bunker he catches too much sand. Leaves himself a 71-yard shot to the flagstick. His pitch is poorly judged, careers on 18ft past the hole. His first putt goes 6ft past.

All around there is consternation, borderline panic.

“Oh, no,” someone says.

“He’s still away,” another adds, lamenting the overhit putt.

“And he’s now going to show Bryson the line,” a third almost sobs.

He makes double bogey. DeChambeau makes par.

Just one hole to obliterate his two-shot lead.

Inside his head the demon taunts him: how does it feel without a cushion?

And he says: “More comfortable, actually.”

Battle has commenced. Sport’s Kramer vs Kramer. McIlroy vs McIlroy.

Walking down the second fairway I fall into conversation with Rob Nolan from Seattle. He tells me he played Augusta Country Club earlier in the day. Went round in 84, is pleased by that. Rob is a young-looking 50 and everything he says speaks of a sensible bloke. I ask whom he is rooting for? “Rory, of course Rory. Rory needs to win this, for mankind.”

McIlroy was the firm fan favourite on his day of redemption

REX

“Mankind,” I ask?

“I mean Rory needs to win for the game of golf and for mankind in general,” Rob repeats. OK.

He is now preparing to play his pitch to the 3rd, a short par-four and one of the truly great holes on the course. Place the pin in the middle of the green and it’s a hole every pro feels they should birdie. But this is Sunday at the Masters and the pin is front left on the narrowest section of an elevated green. Wicked.

McIlroy pitches his ball into the bank, 10ft to the right of the cup. The ball then takes the right-to-left break, trickling in a lovely arc down to the hole, leaving him a 9ft putt for birdie. A putt with plenty of left-to-right break. Afterwards he will be asked what he considered the best shot of his round.

“The best shot I hit today? It could be the second on 7, but I think the most, one of the most important ones for me, was the second shot on 3. You know, I started six, five. Hit a good tee shot on 3. That’s not an easy second shot, bumping it up that hill. To judge that well and make a three there, when Bryson then made five, and then to go ahead and birdie the next hole, as well, that was, you know, it was very early in the round, but it was a huge moment.”

McIlroy’s nationality mattered not a jot to the largely supportive Augusta crowd

MIKE SEGAR/REUTERS

Every demon has a plan until punched in the mouth. This is McIlroy saying no matter how many bad things happen, he is not taking them lying down.

At the back of the par-three 4th green I stand hopelessly far back as he takes a five-iron from his bag. There are ten rows of patrons parked directly in front of where I want to be. It is time to pull an old trick, one discovered in relative youth and never meant for use in later years. Necessity is the mother of reversion. “Excuse me,” I say, “I just need to get to my seat at the front.”

These are polite folk. They part, I walk through and have a perfect view as McIlroy’s tee shot comes out of the sky. “It’s gonna be good,” the man next to me says and everyone cheers as the ball drops and settles pin-high a little left of the hole. Another nine-footer for birdie. Again he makes it. So much talent.

What happens after he hits his drive on the 7th into the trees tells about the crazy player he can be. Sometimes fragile but so often fearless. Harry Diamond, his caddie, tells him not to think about it. They met on the practice green at Holywood golf club when McIlroy was seven, became friends and here they are at Augusta National one more time.

Diamond wants him to take his punishment, hit a safe low shot and just get out of there. He’s always been like a big brother to McIlroy.

This was the ludicrously small gap through which McIlroy played his recovery shot on the 7th

“I probably shouldn’t have taken it on but I was like, ‘No, no, I can do this.’ Anytime I hit it in the trees this week, I had a gap. So I rode my luck and you need that little bit of luck to win these golf tournaments. With the things that I’ve had to endure over the last few years, I think I deserved it.”

Everyone laughs when he says this. If there’s one player on the planet who deserves to catch a break, it is him.

At the back of the 8th green I shoot the breeze with Russell Leonard, who for more than 40 years has been coming to the Masters from his own home in Tennessee. He tells me he so wants McIlroy to win. I again ask why. “What he’s been through. Here in 2011, at the US Open last year against DeChambeau, at the Open Championship in 2022.

“I first came here in the Eighties. My father used to take me. What we’re seeing here today, this support for one player, it reminds me of Jack Nicklaus in 1986. People so wanted to see that happen. It’s the same today.”

McIlroy made a birdie on the 9th hole to pull away from DeChambeau

MICHAEL REAVES/GETTY

By the left side of the 9th green I fall into conversation with two young men, Mike Sofka from Cleveland and Drew Doleski from Chicago. They too want McIlroy to do it. You want an Irishman to beat an American favourite, I say, because DeChambeau is still alive at this point. “Rory’s been playing over here so long, people forget where he’s from. He’s just Rory.”

Walking down the right side of the 10th fairway, the strangest thing happens. I meet a couple that I’d first met on this same fairway on the Sunday of the 2011 Masters. We were three Irish people, part of McIlroy’s triumphal march, or so we thought. He’d had a four-shot lead at the start of the day. It didn’t take long for us to become part of a funeral procession.

Memories of McIlroy’s 2011 heartache reared their ugly head as he wobbled early on the back nine

ROB BROWN/AUGUSTA NATIONAL/GETTY

A few years later they told me the story of their Masters passes. To protect both the living and the dead, I shall not use their names, though I know their story to be true. They had a priest friend in the midlands of Ireland who became involved with a married woman, the wife of a pillar of the community.

As scandals go, this was far from humdrum and the bishop had to act decisively. He decided the best solution was to relocate the rogue priest. The man was sent to a parish in Augusta, Georgia.

He loved his time there and made many friends. One couple he knew decided to holiday in Ireland. As the priest was back home at the time, he promised to look after them once they arrived. For whatever reason he wasn’t in a position to honour that and asked a friend if he could drive to Limerick, pick up the couple and take care of them. This friend was the man I first met at Augusta in 2011, whose name I dare not mention.

For a week they took the American couple here and there. On the last night, over dinner, the Americans said: “Look, if ever you’d like to come to the Masters, you could stay with us in our home and use our tournament passes.” That was the autumn of 2007 and the Irish couple went to their first Masters in 2008 and then every year until 2015. It’s an ill wind that doesn’t blow some good.

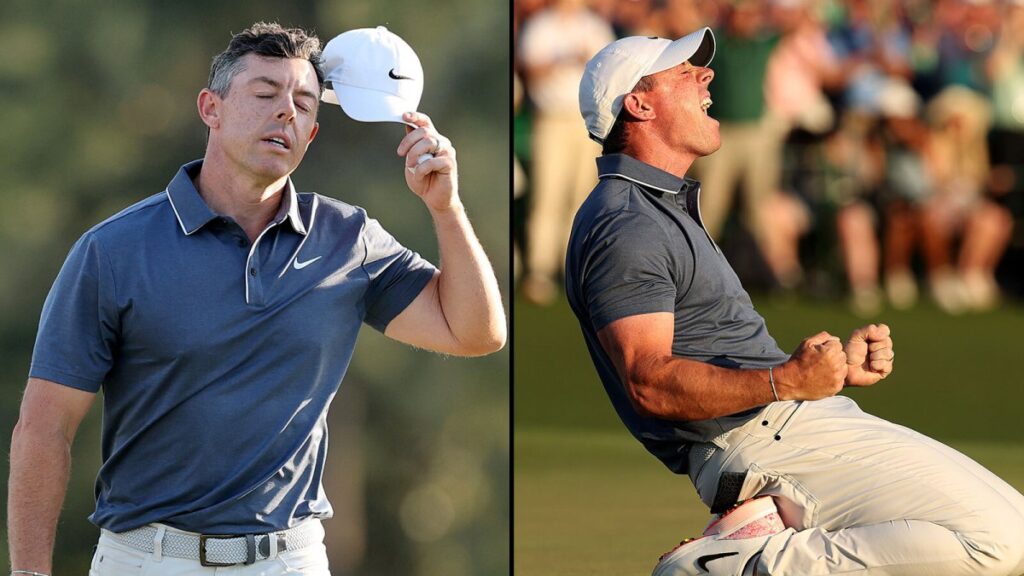

McIlroy gives full vent to 14 years of pent-up emotion as a delighted Diamond looks on

MIKE BLAKE/REUTERS

By 2015 the kind Americans had both died and their two Irish friends no longer had their invitation to the Masters.

Last September the family of the deceased couple got in touch. “If you’d like to come to the 2025 Masters, the tournament passes are yours.” Ten years after their last, they returned. We walk down the 10th fairway as we had in 2011. Back then McIlroy had made a triple-bogey seven at the 10th. Now he makes birdie. Golf may be the most unfathomable pursuit known to mankind.

After McIlroy makes two excellent pars on 11 and 12, he leads by three. A woman down at Amen Corner says: “All Rory’s got to do from here is play dee-fence.” The tall man alongside her shakes his head. “Rory can’t play dee-fence. I hope Justin Rose beats him.” He says his name is Brooke Horsting and that he is from Charleston, South Carolina. Why is he hoping for Rose to win? “I just don’t want Rory to win because then all the drama is done.”

I think of Brooke on the next hole, the par-five 13th, because he is right. Rory isn’t good playing dee-fence. A three-wood off the tee, a safe lay-up at a hole that he regularly goes for in two. His third shot seems a straightforward 80-yard pitch, one to start left and let it funnel down to the hole. He mis-hits the pitch, too far right and it’s swallowed up by Rae’s Creek.

Please enable cookies and other technologies to view this content. You can update your cookies preferences any time using privacy manager.

This blow to the solar plexus literally brings him to his knees. Demons finding a way. Double bogey. He will speak afterwards about the good fortune he enjoyed over the four days but the bogey on the very next hole, the 14th, was cruel. His excellent putt sat over the right lip of the hole. It had to fall, except it didn’t. McIlroy the hunted was now the hunter. His back to the wall, the seven-iron approach to the 15th green was his most spectacular shot of the day, one of those McIlroy moments where he makes the difficult appear straightforward.

So, too, with the brilliant approach to the 17th that allows him to regain the lead. Then the demons play their last card and force him into a play-off with the admirable Rose. But the absolute last blow will be struck by him, the gap wedge to four feet, and the prize that he most wanted is his.

The newest owner of the Green Jacket shares the limelight with his wife, Erica, and their daughter, Poppy

MIKE SEGAR/REUTERS

I had stood at the back of the 17th green, marvelled at the purest eight-iron approach you could ever see.

Time now to head down the 18th but the crowd lining the fairway is ten deep, 30 deep around the green. Thousands stand behind the green, all the way back to the first fairway. No one can see a thing. No one has a phone, no one has a clue. I rush back to the media centre. Two Securitas women are on the door of the media centre, one looking at a TV. “Oh no,” she’s says, “he’s missed. There’s going to be a play-off. I don’t know if I can watch this.” They were all rooting for him.

Thinking this might be my last Masters. In a way, I hope it has been. For, as Melvin Udall, played by Jack Nicholson, said to the people in the psychiatrist’s waiting room in James L Brooks’s 1997 film, “What if this is as good as it gets?” It certainly was that.